What did I Learn from my Skepticism?

A review of the series and of my thinking

Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy! I’m James and I write mostly about education. I find it fascinating and at the same time maddening. Scholastic Alchemy is my attempt to make sense of and explain the perpetual oddities around education, as well as to share my thoughts on related topics. On Wednesdays I post a long-ish dive into a topic of my choosing. On Fridays I post some links I’ve encountered that week and some commentary about what I’m sharing. Scholastic Alchemy will remain free for the foreseeable future but if you like my work and want to support me, please consider a paid subscription. If you have objections to Substack as a platform, I maintain a parallel version using BeeHiiv and you can subscribe there.

Let’s not waste our own time

The last five Wednesday posts have featured my skepticism of a topic or influential idea in the education space. I started out by touching on the recent history of one influential but wrong idea, learning styles, because that’s a model for what I hope schools can avoid going forward. As a field, education is full of zombie ideas that simply never go away. It’s incumbent upon educators, school leaders, and policymakers to try and avoid wasting time, effort, and money on initiatives that may not have a lasting impact on schools or kids’ learning and wellbeing.

Do Learning Styles Really Exist?

In general, most learning style theories make two presumptions:

Individuals have a measurable and consistent “style” of learning, and

Teaching to that style of learning will lead to better education outcomes, and conversely, teaching in a contradictory method would decrease achievement.

In other words, if you are a visual learner, you should learn best if you see things, regardless of the situation. If you are a kinesthetic learner, you will learn best if you can physically manipulate something, regardless of the topic. However, neither of these two assumptions shows any grounding in research. These two propositions are where we can see the concept of learning styles breaking down.

When I was going through teacher preparation, learning styles were part of that preparation. I, and probably many other future educators in the 90s and early 2000s, spent time building lessons and content aimed at reaching kids’ learning styles when we could have been doing other things. Moreover, if we went into classrooms and leaned heavily on learning style theory, then we may have hindered kids’ learning rather than helped. Teachers have every right to feel misled and doubt the usefulness of their training when stuff like this happens! Schools have every right to be skeptical of proposed initiatives and reforms when they’ve failed to yield results.

The problem, then, is how do you know ahead of time if something will fail to produce the desired results? My goal in airing my skepticism was not necessarily to disprove any of the ideas I wrote about but to point out where evidence was lacking, unconvincing, or where the underlying theory of action just didn’t make much sense. To me, these ideas are ripe for becoming the next learning styles debacle. I’m going to embed the posts below and then dive into a more reflective writeup about my own thinking.

I'm Skeptical: Learning Loss

Many of the foundational assumptions around post-pandemic learning loss seem half-baked and could use some fleshing out by those who wish to continue with the concept. We should take the warnings from the poor replicability of summer learning loss and the limited usefulness of post-disaster learning loss to heart. This is, of course, the lesson of scholastic alchemy. Policymakers and educators want to help kids learn and recover from the disruptions of COVID. They adapted a measure of summer learning loss (already disputed!) and began trying to spin gold from lead. One of the big responses to learning loss was to implement tutoring but academic results have been mixed and programs are struggling with attendance, including when tutoring was in-person. A seemingly simple problem seemed to have a simple solution, but it never quite panned out.

I'm Skeptical: Personalized Learning

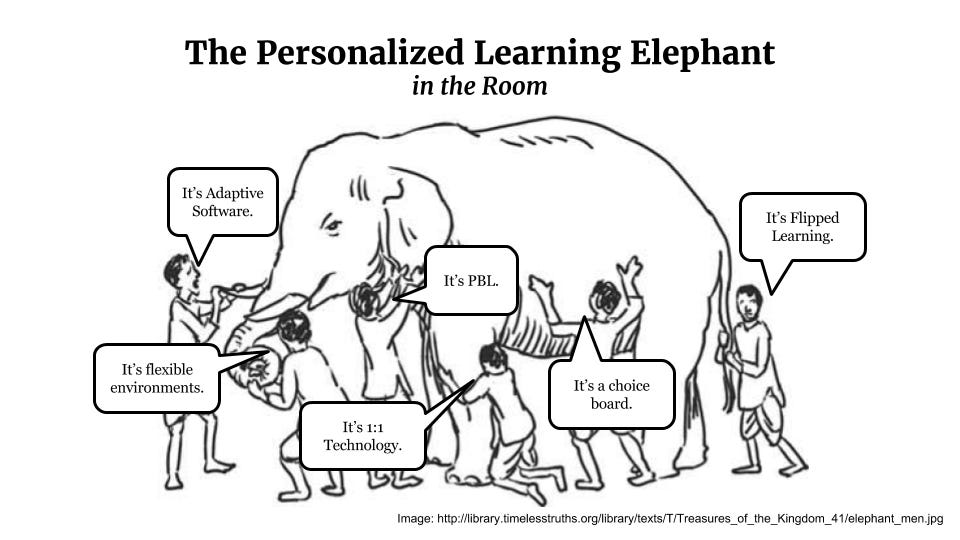

The chimeric quality to personalized learning often means its proponents start to make arguments that sound an awful lot like true personalized learning has never been tried. The better AI or perfect curriculum model or move to mastery-based gradeless education are always just around the corner. That thing over there that you say didn’t work, yeah, that’s because it’s not really personalized learning.

I'm Skeptical: Science of Reading

SoR is expected to be the one neat trick that turns around our schools, but it’s also embedded in a reform structure antithetical to schools’ mission. SoR is supposed to work wonders for readers, but older readers don’t seem to benefit because comprehension is given a back seat and we don’t see test scores budge. Other useful components of reading, such as building background knowledge and vocabulary don’t receive as much focus from schools as they should, in part because fights over SoR are, so to speak, sucking all the oxygen out of the room. Once again, we have a setup where the lauded reform seems destined for mediocre results.

I'm Skeptical: Engagement and Motivation

Proponents of engagement and motivation pretty much always assume that if we develop engagement then outcomes will follow. What if the opposite were actually true? What if students only developed motivation and a sense of engagement because they were successful in school? What if what kids really need is the knowledge and skills to succeed because that also pays psychological and social dividends that we measure as engagement and motivation? What if efforts spent on building engagement or motivating students were better spent on improving student outcomes?

I'm Skeptical: Tutoring

We’re told that tutoring is the gold standard and that everyone should learn from tutors just like Alexander the Great did. A review of the actual history shows us that tutoring is a second-best alternative to what the classical Greeks actually preferred, schools. Interestingly, reviewing the modern evidence about tutoring tells us something similar. On its own, well implemented tutoring programs under controlled conditions with students well-suited to tutoring (e.g. college upperclassmen) really do seem to produce some of the best outcomes of any intervention. When you scale the program, you lose some efficacy. When you take the program outside the conditions of an academic study and into k-12 schools, you lose some efficacy. When you put the tutoring online instead of in-person, you lose some efficacy.

Learning happened?

One reason I write is to better understand what I think. In each of these posts, I often started with some skeptical ideas that I later jettisoned as I read more, thought more, and wrote more. For example, I expected there to be a clearer standard for what counts as personalized learning in the research literature. Yes, of course out in the world we have to expect lots of people to label things personalized learning that maybe are not personalized learning. As I looked through studies and literature reviews, it became clear to me that, no, there was no standard in the academic research community either. I was shocked, in fact, to find researchers basically giving up on whether personalized learning actually had impacts on learning. This led me to reorganizing my post and writing more about how meaningless a term like personalized learning really is. So, let’s make that a principle of my skepticism.

Education Skepticism Principle 1: Big ideas, reforms, and interventions need to have a clear definition everyone accepts that enables empirical evaluation of the idea, reform, or intervention.

Makes sense to me. If you’re going to do a thing, you need that thing to be a thing and not also be a bunch of other things. If your thing is all the things, then nobody knows which thing is doing anything and we can’t tell others which things they should be doing.

Directionally correct?

If I were to distill another principle, it would have to revolve around assumptions of causality. The research on engagement and motivation shows a clear correlation between students’ academic performance and their engagement in the classroom as well as their motivation to learn. And I don’t dispute that correlation! The problem is, most approaches assume the causality flows in one direction, from engagement/motivation to academic performance. That is not, however, what the data show. Studies only show that academic performance is connected to engagement/motivation. Moreover, attempts to show the reverse causality are also successful: better academic performance leads also to more engagement/motivation. If the studies of the correlation between engagement/motivation and academics demonstrate the causal connection flows both ways, then what you’re really saying is that the relationship is complex and that there may be other important unmeasured effects in the mix that are driving the real causal relationship. This is why I’m skeptical that scaling up big programs around student engagement (like tech in schools was supposed to accomplish a decade ago) or around motivation (such as grit and mindset exercises) will lead to systemic and measurable gains in real world settings. What’s the principle here?

Education Skepticism Principle 2: Big ideas, reforms, and interventions need to demonstrate a plausible causal relationship with student outcomes, school improvement, or other desirable development.

I get that this is a big ask. Social science is hard and, especially with schools, it’s really difficult to get slam-dunk causal evidence that an intervention works. What I think would be a good step is efforts to study potential causal flows in both directions. If you say you are confident that intervention A leads to desirable outcome B, then I’d like to see you checking whether outcome B doesn’t also lead to the conditions set up in intervention A. Obviously not all ideas, reforms, and interventions work this way (e.g. if claiming tutoring => high grades it doesn’t make sense to test whether higher grades => tutoring).

Mismeasure?

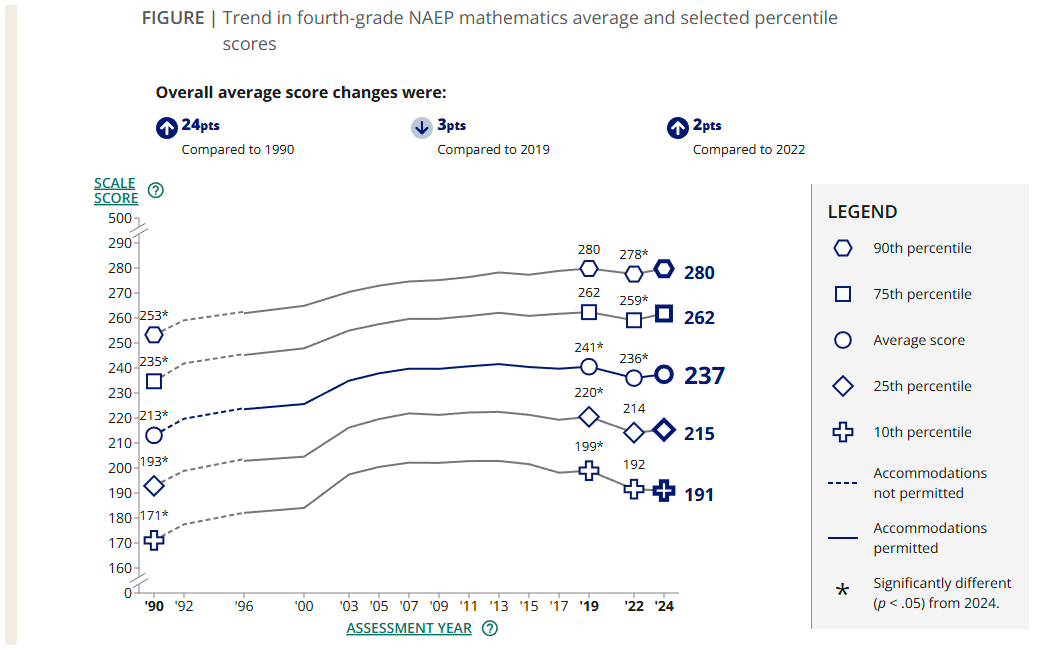

Researchers often need to construct measures in order to study a phenomenon. When looking into learning loss, I was surprised by the arbitrariness of the measure. There doesn’t seem to have been any effort to validate the core learning loss measure: 0.25 standard deviations on a test score equals one year of learning and therefore dividing that number by the number of days in school tells us how much a student should learn on average in one instructional day. In looking at how that number came to be, it really seems like someone at Stanford’s Hoover Institute just picked it out of thin air in 2012. (It’s not a peer reviewed publication but a white paper by the highly ideological conservative thinktank.) Then, others at Stanford’s CREDO institute ran with it (Again, CREDO is an institute established to promote charter schools, so we’re dealing with a measure that originated in two organizations that seek to damage public education.) Amazingly in that same 2012 report the authors note that on the PISA the US showed 0.46 standard deviations of growth per year, nearly double the “rule” being applied to NAEP scores. Nevertheless, the measure stuck and was applied first to summer learning loss and then to post-pandemic learning loss and now we get nonsensical measures of learning loss such as a report that suggested students cumulatively lost more than thirty thousand years of learning. This is, frankly, nonsense and taking the measure to an absurd conclusion whereby closing schools in some places for somewhere between 6 months and 2 years has caused more learning loss than the entire span of recorded human history.

Education Skepticism Principle 3: Measures used by big reforms, ideas, and interventions have to make logical sense and receive some kind of evaluation of their validity and reliability.

One thing you may be noticing is that these principles build on one another. The first principle requires a clear definition so that empirical evaluation (research) may take places. The second requires causal assumptions within the research to be questioned and evaluated. The third requires measurements researchers use to be credible because otherwise you can’t do number 2 very well.

Sliding scale?

I personally found writing about tutoring to be the most interesting of the articles I worked on in this series (despite the 8k words spent on science of reading, it’s less interesting to me because I already know so much about it). What I liked about it is that tutoring really can be effective in certain circumstances (basically 1:1 tutoring of college kids in a course’s content by grad students with expertise in that content) but it’s also clear that as you move further and further from those circumstances then the tutoring becomes less and less effective. The principle here is one about the challenges of scale.

Education Skepticism Principle 4: Big reforms, ideas, and interventions should demonstrate efficacy at a large scale, such as school or district-wide scales, if not larger.

People often point out that almost no interventions are shown to work at a large scale and they’re right. Some commentators argue that the best bet in education is the Null Hypothesis.

I have argued for what I call the Null Hypothesis with respect to education interventions. That is, when tested rigorously, an education intervention probably will produce a result for the treatment group that is not significantly better than what one finds in the control group. Any apparently significant result is likely to fade out over time. And any lasting result is unlikely to be replicated if tried somewhere else.

I am inclined to agree. Far from being some kind of doom-and-gloom view of education it is, instead, the realization that changing complex systems is hard and that often what exists now is the best possible version that could exist given all the real-world limitations we face. Skepticism is warranted and we should expect most people who take big swings to make big misses. That’s not a failure of schools or teachers or society, it’s just how complexity works. As you scale up, efficacy slides down that scale. If anything, it means we should want more experimentation, but we need to couple it with the sense that the successful ones may only be successful in once place or at one time. That should be okay.

Branding?

The final lesson I’ve learned is less about the research or reforms or initiatives themselves as much as it is about the people who promote them. Some of these reforms have been turned into brands by the people promoting them. The Science of Reading is a prime example. The evidence for including structured phonics instruction in elementary reading curricula is strong. The problem comes when phonics-driven instruction becomes part of an activist movement, adopted by a political movement, and begins to develop into a dogmatic view of how schools should teach reading. When the researchers, the scientists, who study reading are being contradicted by the most vocal proponents of the science of reading, it’s jumped the shark. We’re moving beyond good instruction and being sold a story instead of a reform. Or, look to the tutoring post where I begin with Sal Khan’s use of history to explain the benefits of his product. His history is factually inaccurate but that is beside the point. He’s engaging in marketing for his brand, Khan Academy.

Education Skepticism Principle 5: Big reforms, ideas, and interventions should be justified on the grounds that they work, not because someone can tell a good story about them.

If the first thing someone tells you about their proposed big idea in education is a story, it’s a red flag. The first step should be an explanation followed by an evaluation of the evidence that the thing works. If you begin with the marketing copy, I’m well within my rights to doubt your intentions.

So, there you go! I’ve spent the better part of six weeks engaging my inner skeptic in an evaluation of five big ideas in education right now. There are undoubtedly other ideas out there and I am not aiming for an exhaustive series so much as a thought exercise. I would really like to live in a world where tutoring and the Science of Reading and personalized instruction and student engagement all led to dramatic improvements for schools everywhere. Perhaps they could bring an end to the thirty millennia of learning loss we are apparently experiencing. But they probably won’t. Going forward, it’s worth taking these five principles of educational skepticism seriously. They are probably not iron-clad perfect principles. I’m sure I’ve missed things or overstated flaws in some way. Maybe someone will let me know one day in the comments. Still, you could do a lot worse. In fact, we have done worse repeatedly over the recent history of education. Having a default position of skepticism is, I think, actually in the best interests of schools and of kids.

Thanks for reading!