How did we get here: The skills gap that wasn't

How getting human capital wrong meant too much economic focus on education

First, some housekeeping. Welcome to Scholastic Alchemy, a weekly newsletter where I write about education and share a handful of interesting links. My goal, at least right now, is to write about how the US arrived at the current moment in education, a moment where it seems like everything we know and trust about schools is about to go out the window. If you’re interested in this kind of thing, please subscribe. I plan to put up the paywall in early March. If you do not like Substack as a platform, I will be publishing a parallel version using Beehiiv.

Recap: The Human Capital Consensus, Tech, and Phones in School

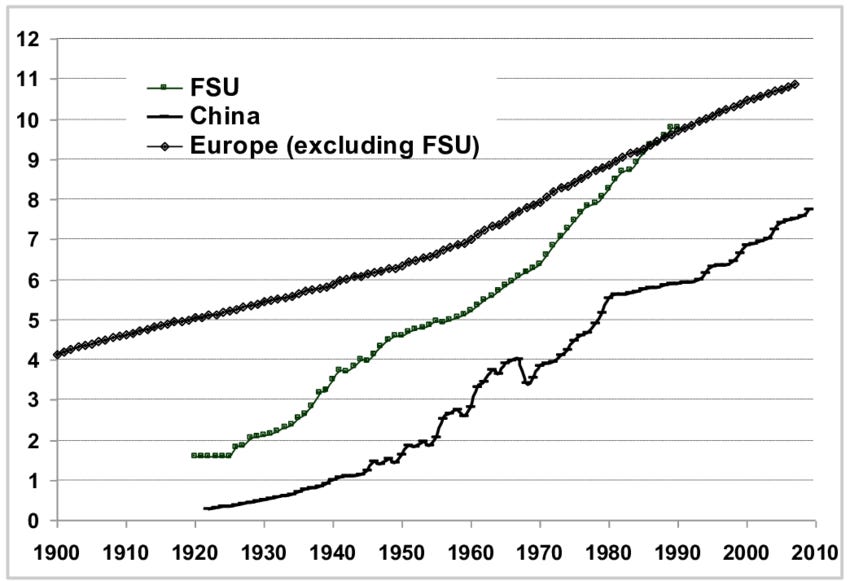

The last two posts were an admittedly clumsy attempt to make an important point about how educational stakeholders — parents, teachers, administrators, district leadership, policymakers, researchers, philanthropies, and advocates to name a few — all coalesced around a view of our system of education as primarily a human capital production machine. I don’t think it’s crazy to say that sending people to school and then some of them on to university makes their lives better in the long run. They learn things. Those things are useful throughout their lives. That learning enables a certain kind of success in the workplace which benefits both the workers and the employers and, by extension, the economy as a whole. I also spent a bit of time trying to disentangle Human Capital Theory from neoliberalism by pointing out that much of the data used to create the theory predates the neoliberal turn and that much of the literature on human capital has been used to identify the economic loss we face when discriminating and segregating on the basis of race and sex. (As a side note, I came across an interesting article recently that sought to identify human capital in the USSR and China. While behind the comparator, Europe minus the former Soviets, the commies still saw an accumulation of human capital. Unless the USSR is now also considered neoliberal, I think we can put away this idea that human capital is always a neoliberal construct.)

There is a drawback to the broad stakeholder acceptance of the human capital model of schooling. Human Capital Theory, as an economic theory, is concerned with economic things like labor productivity or worker income but it does not tell us specifically what schools and universities did to bring about those outcomes. Those of us in the world of education had to figure that out in other ways and often turned to industry surveys or university-based and philanthropically funded think tanks. Both turned out to have a spotty record of predicting which specific skills or what specific knowledge our education system needed to be teaching. Moreover, there was too much emphasis placed on specific skills because we had apparently forgotten that Human Capital Theory posited more gains from general skills.

I argue that this misunderstanding is why we have phones (among lots of other tech) in our classrooms. Somewhere along the line — okay, not somewhere, like 2005-2015 — the trending belief was that kids needed lots of tech in their schools because they would need to be familiar with that tech for success in their careers. Cross-pollinate that with schools’ slow and expensive adoption of 1-to-1 computers/chromebooks, and you can see why phones were seen as a great way to get internet enabled tech into your classroom. We needed to prepare 21st century workers, after all! And who knows, maybe for a few great years they were awesome to have around? Sadly, our phones, and especially the social media applications therein, rapidly improved in their ability to divert and diminish our attention. Although people right now complain about phones in schools and wonder why we could ever have been so stupid, it’s important to remember that we genuinely felt this was essential to our economic wellbeing as a nation. Go back to that Did You Know 2.0 video. It is all about how China and India are going to surpass the US unless we tech up. It ends with a call for viewers to pressure school boards and lawmakers to incorporate more technology in schools. This is, I think, a key specific misunderstand of Human Capital Theory (and include all the requisite qualifiers about how I’m not an economist, just a guy who reads a lot of economics books, articles). Next, I’d like to discuss a more general distortion that I also attribute to misinterpreting Human Capital Theory.

School = The Economy?

Until now, I’ve been using human capital to tell one version of a story about the relationship between education, labor productivity, and the job market. Schools and universities impart general skills (perhaps literacy, numeracy, knowledge of important scientific principles and practices, an understanding of relevant history and civics, time management, and self control, among some other things?) that enable people to be successful when they join the workforce and give them the ability to benefit from specific skills training in the workplace, sometimes repeatedly. This results in a generally better set of circumstances as measured by their income and by labor productivity, which in turn makes the economy better, growing the GDP pie for all.

What if we kind of inverted this story and then turned it inside out? What if, instead of schooling leading to generally a capable workforce, schooling was partially creating the job market and, therefore, driving the economy itself and the economic wellbeing of the populace? When I put it this way maybe it’s a bit crazy sounding, but I’d argue that this is what many important people who make decisions about education policy actually believed. As evidence, let’s turn to an interesting source: the Economic Report of the President. Specifically, reports from the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations. (Long block quotes incoming.)

2006:

Economic research suggests that educational attainment and test scores are important at both the individual and the national level. At the individual level, people with higher levels of education have higher earnings than people with less education.

In addition to income, schooling levels are associated with other positive economic and social outcomes. More-educated adults are less likely to be unemployed or incarcerated than less-educated adults. More-educated adults are healthier and have lower mortality rates than less-educated adults. They are also more likely to have college-educated children, thereby passing the benefits of higher levels of education on to future generations.

Studies have also shown that higher test scores are associated with higher wages and more years of schooling. High school students with higher test scores are more likely to attend college and, if they attend, are more likely to graduate. Controlling for individuals’ educational attainment and family background, those who score higher on achievement tests in high school have higher wages later in life (p.50)

Historically, high levels of education and skills in the United States have boosted earnings for individual workers and fueled one of the most dynamic, innovative economies in the world (p.63).

Note the blending of these two stories. On one hand, education makes things better for workers and employers but on the other hand it sounds like education is directly responsible for the nation’s economy. Because workers’ earnings get spent back into the economy, the economy grows. Therefore, if we accept that education raises earnings, it follows that improving schooling improves the economy. And testing, too!

2015:

By the end of the decade, two in three jobs will require some higher education (p.4)

Economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz (2010) explain this phenomenon as a “race” between technological advancements that increase the demand for highly‑skilled workers and the supply of such workers. In particular, they document a slowdown in the growth of the college educated workforce around 1980. This slowdown has meant that growth in the demand for skills (technology) outpaced growth in the supply of skills (educational attainment of workers) (p.145).

…increased educational attainment, have translated into large income gains for American families and have benefited the U.S. economy overall (p157).

I couldn’t resist throwing in that first line about 2/3 of jobs requiring “at least some higher education” since we’re now a decade away and it seems that this prediction has not come true! Maybe the slowdown in growth was workers responding to labor market conditions because most jobs are low-moderate skill service sector and agricultural jobs, as they have been since the 1980s? No? Anyway, back to the topic at hand, we see the linkage between economic success and educational attainment which I do not dispute, and then the generalization of that success to the economy as a whole. (Yes, I did mention Goldin’s work in my human capital post, and I think the CEA folks writing the report interpreted it wrong.) The story is that the post-Great Recession economy is weak in part because of poor educational attainment. Therefore, we can fix the economy by increasing educational attainment because those people earn more money. At no point is a different case made that the economy sucks and jobs simply pay too little. The macroeconomic conditions of the economy are, seemingly, unimportant. Schools will fix it.

A Gap that Wasn’t

What’s especially interesting writing about this from the 2025 vantage point is how thoroughly discredited this story now is. We got pretty damned close to full employment in 2018-19 and saw wages going up. Hell, even by 2019, you had Vox telling us that the skills gap mentioned above was a lie.

Five or six years ago, everyone from the US Chamber of Commerce to the Obama White House was talking about a “skills gap.”

The theory here was that high unemployment reflected a structural shift in the labor market such that jobs were available, but workers simply didn’t have the right education or training for them. Harvard Business Review ran articles about this — including articles rebutting people who said the “skills gap” didn’t exist — and big companies like Siemens ran paid sponsor content in the Atlantic explaining how to fix the skills gap.

But nothing was really done to transform the American education system, and no enormous investment was made in retraining unemployed workers. And yet the unemployment rate kept steadily falling in 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 as continued low interest rates from the Federal Reserve let a demand-side recovery continue. Donald Trump became president, injected a bunch of new fiscal stimulus on both the spending and tax sides, and in 2017 and 2018 the unemployment rate kept falling and the labor force participation rate kept rising.

MIT beat them to it by two years, arguing that it was not a lack of technological knowledge and skills but low wages and problems with employers’ ability to find applicants because of “inadequate soft skills among younger workers.” There’s those general skills of Becker’s again. Anyhow, Covid-19 hit and caused all kinds of disruptions but as we recovered, we saw the highest levels of employment pretty much ever and rising wages (even accounting for inflation!) with the lowest earners seeing the most wage growth. The human capital situation did not meaningfully change between 2018 and 2024. We didn’t suddenly get that extra 1/3 of “some college required” jobs and then fill them with millions of “some college” workers. Of course, I disagree that “nothing was done to transform the American education system.” We put phones in classrooms. Or, perhaps, you may recall Obama’s signature education achievement, Race to the Top? That was still in effect. A discussion of RttT and other school reforms will have to wait until, probably, next week. Nobody wants a 10,000 word post.

Another way to think about this is to imagine that our government decided to send 1/3 of all k-12 students into the wilderness to learn about camping and wilderness survival for the next ten years. Nobody imagines that the entire US economy will reconfigure itself around camping and that we’ll have a successful camping-driven economy. Sure, there will be some increased demand for camping supplies and knowledgeable wilderness experts, but we still need all the other shit that economies need. Doctors or checkout clerks or whatever. If you said this people would think you’re crazy but if you replace camping with STEM courses and wilderness survival with learning to code, then suddenly you’re a very reasonable and serious person with an important perspective. And that’s, more or less, exactly what the inverse-inside out human capital argument was. Schools beget jobs beget the economy and everything (even our survival as a nation) depends on our ability to get that school/job/economy connection right. The problem is, it just wasn’t true.

This incorrect view, and the misguided focus on specific skills and knowledge, formed the core justification for what we’ll talk about next week, education reform. Importantly, however, I also want to make another case next week. What seemed like market-oriented reforms fronted by a neoliberal ideology was, I think, part of a decades long conservative effort to remake schools along religious and racial lines. There’s an important reason we paused on the revanchist school movements of the 1970s and 80s: an informal treaty between liberals and conservatives that limited changes to what we now consider neoliberal.

Links

*Note: usually but not always about education

Although I plan to go into more detail next week, this recent article from Pro Publica shows the strong connection between school reform, conservative causes, and religion in Ohio. It was never about school choice and the efficiency of the market. The Church wants your tax-tithes, will play the long game to get it, and will use whatever tactics it needs along the way.

I don’t have a super solid opinion on this research or the arguments rebutting it but it’s probably worth following up when a top scholar says evidence for inclusion of special education students is flawed. You’ll see in the article that it’s mainly a methodological criticism of the research literature and a point that we know less about successful inclusion than we think. What I expect will happen is that opponents of inclusion, people frustrated by a strained system, and conservative privatizers will use this as an excuse to gut special education more broadly. Which is too bad because 15% of our students have some kind of disability. That’s a lot of kids and families.

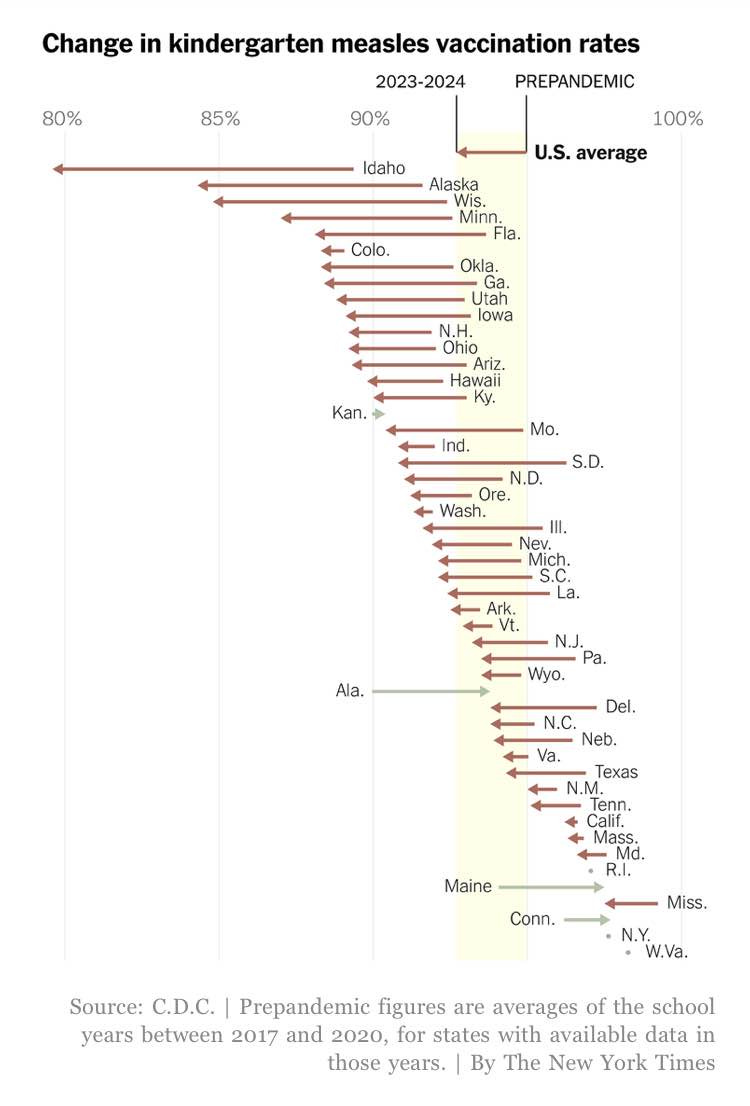

Speaking of problems with long-term consequences: childhood vaccination rates are falling. This is, actually, very closely related to one of the points I made last week. Human capital includes the health of the workforce. A sicker population is not just a less educated one (as the article points out), it’s also just plain sicker. My kiddo was sent home with a fever last Friday. Turns out she had the flu. Because she was vaccinated, her course of illness was less severe and shorter than it otherwise might have been. She could have gone back sooner except for some rules about how long after a fever kids have to stay home. I would prefer kids are less sick. I would prefer to be sick less often and with less severity. Sadly, that’s not the world we’re headed towards.

I was speaking with a friend of mine over the holiday season and he mentioned hearing an NPR piece a while back about sending kids to school only 4 days a week. What I find interesting in that transcript is:

GONZALEZ: Kennedy is a big Texas Rangers fan, loves pink, soccer, and she is a proud, straight-A fourth grader.

KENNEDY: I never fall behind.

GONZALEZ: Ooh, they like that.

In China Spring, Texas, there is no school on Fridays anymore. Instead, she gets dropped off at a church, which she says is not fun.

KENNEDY: My favorite part is when we go to the library and watch a movie.

GONZALEZ: Oh, you get to watch a movie?

KENNEDY: Yes, every Friday.

GONZALEZ: Oh.

KENNEDY: We'll usually go in there twice. And sometimes we don't finish the movie, but last time we did watch two movies.

GONZALEZ: So it's, like, really, definitely not like school.

KENNEDY: No, it's way different.

GONZALEZ: It's daycare, and it costs money.

KENNEDY: It's hard financially because it's, like, $45 a Friday for me to go.

JESSICA MONTGOMERY: Yeah, $45 every Friday.

GONZALEZ: This is Kennedy's mom, Jessica Montgomery.

MONTGOMERY: It's just to keep your kid alive.

GONZALEZ: China Spring voters also wouldn't raise taxes to pay teachers more. And now the community basically gets, like, 20% less education for their community with their tax dollars. So the taxes are the same, everyone just gets less out of it now. If the tax hike had gone through, homeowners with, take a house worth $200,000, would have paid less than $60 extra a year. Kennedy's mom now pays $1,260 extra a year in this Friday child care. And this is kind of a tax.

PAUL THOMPSON: So this is definitely a tax on parents.

This kind of reasoning is crazy to me! You’d rather spend $1200 than $60? And not only that, you’re spending more to get less for your kid? She just goes and watches movies at the library or go to church? (I bet the churches are pleased!) I feel like we should want more than “just to keep your kid alive.” It’s bad for student outcomes, as you might imagine:

We estimate significant negative effects of the schedule on spring reading achievement (-0.07 SD) and fall-to-spring gains in math (-0.05 SD) and reading (-0.06 SD). The negative effects of the schedule are disproportionately driven by adoptions in non-rural schools and are larger for female students.

Lest you think I am anti-technology because of my criticisms here, I thought I’d share another newsletter I like to read that offers excellent uses for ed-tech. Oh, wait, it’s the same one I linked last week that also heavily criticized the online-only AI “teacher” charter school that just got permitted in Arizona. Turns out, lots of people love tech in schools but are also keen to call out BS:

I taught for the better part of a decade, occasionally successfully, often badly, but never for lack of trying. It’s just hard. It’s hard, cognitively, to help a novice understand anything new. And it’s especially hard doing that work with lots of novices in the same room all within the tight social and economic constraints of 2025 America.

So as a general rule: if you tell me that you can swap a skilled teacher for a chatbot on a Lenovo Chromebook, if you tell me that the work of teaching is anything so trivial, I am going to take that personally and I am going to pull your card.

He gets my sub. Makes an interesting observation at the very end about Gates Notes (Yes, Bill Gates) erasing some comments he’d made about AI, or was it Personalized Learning? No, maybe it was digital tools or adaptive learning software? Anyway, he gives us this great image that I hope is shared widely:

And that’s all for today. Have a great week! Thanks for reading.