Technocratic Education and Its Discontents (part 2)

What the framework says about education

Hi! This is Scholastic Alchemy, a twice-weekly blog where I write about education and related topics. Wednesday posts are typically a deep dive into an education topic of my choosing and Fridays usually see me posting a selection of education links and some commentary about each. If Scholastic Alchemy had a thesis, I suppose it would go a little like this: We keep trying to induce educational gold from lead and it keeps not working but we keep on trying. My goal here is to talk about curriculum, instruction, policy, public opinion, and other topics in order to explain why I think we keep failing to produce this magical educational gold. If you find that at all interesting, please consider a paid subscription here, or at the parallel publishing spot on Beehiiv. (Some folks hate the ‘stack, I get it.) That said, all posts are going to remain free for the foreseeable future. Thanks for reading!

Before starting, I have to apologize. After last week’s post, a reader let me know that I missed the opportunity to make a different allusion with the title, an allusion that would have been more appropriate given that I write about education: Technocracy and Education. Obviously, a Dewey reference would have been perfect and some of the material concepts of Democracy and Education hew closely to Gratton and Edenhofer’s theoretical framework. Sadly, a section heading with that title is the best my readers will receive.

A Quick Recap

If you didn’t look at last week’s Part 1 post, I’m responding to two themes that emerged over the first year of writing Scholastic Alchemy. The first was something I wrote about almost exactly a year ago, the “charter school treaty.” I used this idea of a treaty to help explain what’s changed politically around education and why reform movements have become so extreme in recent years. Second, and more importantly, I am responding to the seeming inability of liberal (and some moderate conservatives like David Brooks) education commentators to understand that the political landscape has changed. Again and again, I feel like there’s an underlying assumption that all the US education system needs is to return to the 2000s era standards and accountability framework but never an acknowledgement that this change might be largely impossible because both the public and the political class have changed their views on education. Maybe some other explanatory approach is needed? Maybe what these moderates and liberals need is a better model for explaining what’s changing in the world of education?

I brought in two frameworks that I think are complimentary. The larger and more formal model is Jacob Edenhofer Gabriele Gratton’s model of tensions between technocratic and majoritarian tendencies in democracies. That’s the one I’ll be primarily writing about today in relation to education. The other framework was Martin Gurri’s Revolt of the Public. Gurri argues that today’s information rich digital environment creates the conditions of populist revolt. Elites no longer control the flow of information, authorities and experts are not trusted and their efforts to re-assert authority and govern through expertise prove counterproductive because the public can always find information to the contrary that they would prefer to act on. The more authorities try to exert their authority, the more the public resists and this causes revolts. They may take the form of actual revolts like the Arab Spring, or they may be in the form of empowering populist anti-establishment leaders who promise to break elite institutions. I’ll wrap Gurri’s theory back in later on but in general where I see this kind of information problem appearing is with constant drumbeat cycling of “evidence based” and “scientific” curriculums that are appearing not through elite or expert driven guidance but through public activism and social media virality. For example, we have given so much attention to the Science of Reading not because of what experts have found in studies (and what the experts say is also somewhat different from what the advocates want) but because of a journalist’s popular podcast. The policies are, in many cases, downstream from the digital media and the activism.

I suppose I should also note that I am not an economist or political scientist. I am not attempting to communicate a single comprehensive worldview. I am sure that there are key elements of these theories I may be misapplying or misunderstanding and, if any subject matter experts care to comment and correct me, I’m open to that! I like learning and sometimes that means putting ideas out there in whatever form they have now, even if it’s potentially not perfect or correct. The goal here is merely to provide an explanatory framework that I can use as a reference point to help readers understand what’s happening in education.

Technocracy and Education

In order to understand how Edenhofer and Gratton’s framework applies to education, it’s worth understanding how they talk about the role of technocrats in a democratic society and why they are in tension with populist majoritarians.

Our key assumptions are that unelected technocrats (i) pursue goals that differ from current majority preferences and (ii) weigh minority welfare more than majority rule. The first assumption is sufficient to explain all our constitutional dynamics. The second generates what we call the “lure of technocracy” and explains why technocratic democracies arise as a form of intertemporal insurance against the worst-case scenario of becoming an unrepresented minority in the future.

I have a lot of questions for the authors around what constitutes a majority in their conceptualization and whether a group can be a majority in self-conception even if they are not a numerical majority of the population or electorate. Like, can a group imagine themselves to be a majority because they believe other majorities are illegitimate and then act like a majority movement? But, for the time being, let’s consider the idea of a majority to be a political majority as opposed to a racial, ethnic, cultural, socioeconomic, or other kind of majority. I think this is accurate because later on in the paper they reference some of Gratton’s earlier work along those lines.

As emphasized by Gratton and Lee (2024a), informational asymmetries (also Crutzen et al., 2024) can engender waves of populist reforms that lead to more majoritarian and less technocratic democracies. In their model, preference misalignment between the majority of voters and technocrats fuels voter demand for leaders who promise to “drain the swamp” by dismissing technocrats, even when such purges imply large (efficiency) costs for voters (Gailmard and Gailmard, 2025). Thus, our decision to abstract from informational asymmetries is best seen in conjunction with this work. We identify the conditions under which misalignment arises, leading to pro-majoritarian waves, and when, instead, greater alignment leads to pro-technocratic reforms. In practice, when we identify the emergence of pro-majoritarian reforms, we implicitly assume that a process akin to that described in Gratton and Lee (2024a) is set in motion.

p.6

Note the informational asymmetries! You can see why I also have Gurri in mind when I am reading this.

So, why do I think this explains so much about the politics of education? Well, think about the movement of education policy starting with No Child Left Behind. Was this a majoritarian policy or was this a technocratic one? I think it’s pretty clearly a technocratic one. Elected officials may have written the legislation, but NCLB largely moved decisions out of the hands of local schools and into the hands of state governments. Moreover, it was unelected officials within state governments in conjunction with test publishers who created the systems that governed every child’s day-to-day learning. A decade later, Common Core comes along and implements another policy reform that moves control of schools into the hands of technocrats. Unelected expert authors from both academia and the private sector, backed by hundreds of millions in philanthropic money, created the standards and then those standards were used by curriculum and testing publishers for instruction and NCLB accountability. While, yes, state legislatures had to vote to adopt these standards, the result of that vote was the movement of policy authority and important local school functions into the hands of unelected technocrats. Your elected school board could not change the standards or the tests or the accountability processes set in motion by insufficient scores on those tests.

The other thing that qualifies this as technocratic in Edenhofer and Gratton’s framework is that all of these changes were explicitly justified in minoritarian terms. The language used to sell NCLB and Common Core was one of addressing the educational outcomes of minorities. Even today, when liberal-centrist minded reformers lament the supposed loss of school accountability, they argue for it based on improving outcomes for minorities. In reality, school accountability never went away but has changed forms. Even with the Every Student Succeeds Act, schools continued to operate within a largely technocratic system where state education agencies set classroom standards and established accountability systems. Since its repeal under the first Trump administration, states have continued to maintain technocratic authority over public school curriculum, testing, and increasingly classroom instruction as opposed to delegating that authority back to locally elected school boards. Accountability systems in nearly every state evaluate schools based on the performance of poor children, children with disabilities, children from racial or ethnic minority groups (even though taken together white students have been the minority for many years they still constitute the largest plurality of public-school students), and children who speak languages other than English. Meanwhile, at the federal level, courts and the department of education during the Bush and Obama years expanded protections at school for LGBTQ youth, students with disabilities, and racial minorities, often building on top of decades old legislation that was never properly funded or where enforcement was left up to jurisdictional contests between state and federal education agencies.

It’s really important for me to say at this stage that I’m not necessarily objecting to these changes or fully supporting them either. I’m quite happy with an education system that works to improve outcomes for various minority groups even if I have some problems with the ways in which we went about it. What matters here, though, is how all this looks under the Edenhofer-Gratton framework. Policy changes come with a policy focus and for decades education policy focused on the lowest performing students within various minority subgroups and then on protecting the rights of other minority groups. Schools themselves were not empowered to enact these changes, nor were locally elected school boards. Rather, states empowered unelected experts and bureaucrats, some outside of government entirely, to set the rules and enforce accountability. In other cases, judges appointed to federal courts issued rulings that overrode local control and placed burdens on schools to live up to legal standards set by that federal ruling.

Revolt of the “Majority”

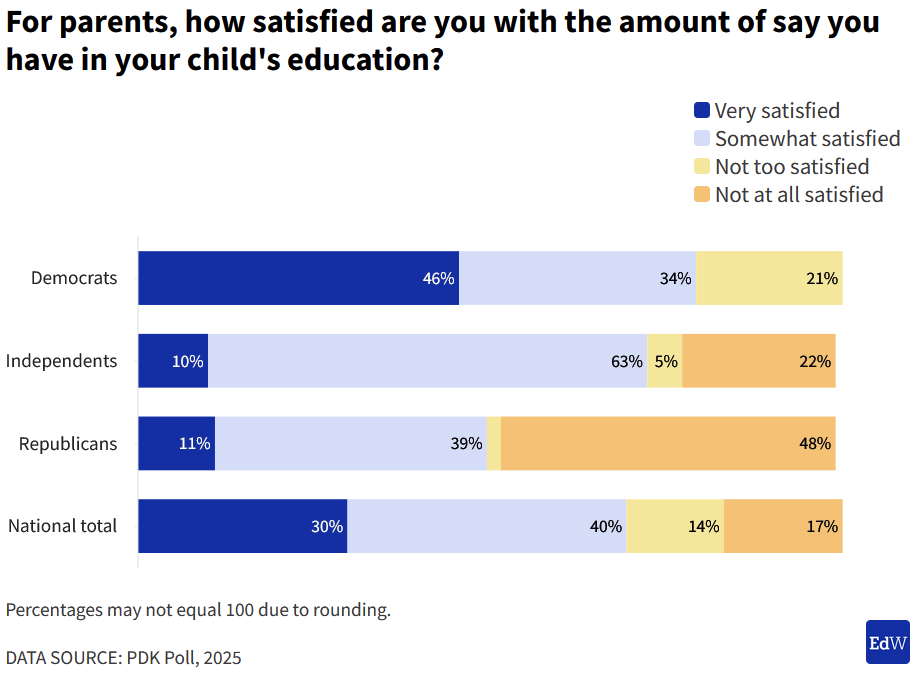

I have discussed before that this loss of control at the local level likely contributed to the public’s rejection of standardization. The main theme of the public’s discontent is summed up by the findings around “having a say” in the 2025 PDK poll.

A good portion of the public feels like they do not have adequate input into their child’s education. Decisions are made about their child without parents being able to have any input. What’s more, the more conservative — perhaps the majoritarian leaning populist — portion of the population feels this lack of “say” the most strongly. Previous polling in the PDK series has found strong public and parental support for the local schools and their employees, including a majority of the public (53%) and strong support among parents (83%) for teachers going on strike in order to get more control over “school standards, testing, and curriculum.”

Within the Edenhofer-Gratton framework this is pretty clearly majoritarian blowback that is resisting the technocratic management of schools and seeking to reestablish a sense of local control and locally accountable decision making. I think they give us an image of populist policymaking that matches what we’ve seen in education:

…populists differ from technocrats because they commit to a specific policy rather than to a rule that, over time, ensures the implementation of welfare-maximizing policies. Populists also differ from mainstream political parties. By committing to simple policies, populists can appeal to voters who distrust politicians’ ability to devise policies—often with the help of experts—that adapt to changing and complex circumstances. On the technocratic–majoritarian spectrum, populists clearly align with the majoritarian pole, but remain distinct in their preference for simplicity and rejection of expertise.

p.7

This is pretty much exactly what’s happened and where I think liberal-moderate education commentary misses the boat. Because populists are able to capitalize on the majority’s distrust of the technocratic system, they’ve been able to push through some simple-to-understand education policies: universal school vouchers. Rather than do what the majority wants, which is empower local school boards and give parents options in a comprehensive school setting, they’ve proposed a system to get key supporters of populism a way to exit public schools and receive public subsidy to do so. In some ways this satisfies parents because the government can say “look, you have total control of your child’s education,” but it is also clearly not welfare maximizing as the reality of having those choices is far from universal and depends on things like whether the private school will admit you or whether you can cover the additional costs beyond what the voucher money pays for. In the meantime, just as the Edenhofer-Gratton would predict, public schools as institutions are under threat. They are at risk of financial collapse as voucher schemes siphon away money while also suffering funding loss from populist property tax revolts masquerading as fiscal relief for seniors. Populists are eager to be rid of public education entirely while conservative reformers would prefer to see a parent choice system that promotes their brand of Christian moral values.

Complimentary Frameworks

The other thing I like about the Edenhofer-Gratton framework is that it compliments, rather than contradicts, the framework I relied upon all of last year, Menefee-Libey’s idea of the charter school treaty. What this new framework does is explicate why majorities grew frustrated under the treaty and why they were do ready to empower populists to smash the whole thing. One of the unresolved tensions of interpreting school policy as a treaty was understanding why each political “side” felt like the treaty was violated. Indeed, if you read all those posts and subsequent ones that referenced them, you may have noticed the difficulty I had in keeping straight political groups like conservatives, the right-wing, republicans in their negotiating of the treaty with democrats, the left, and liberals. When framed this way it was always an open question as to who felt the treaty was being violated and by whom but under the new technocracy vs majoritarian framework the violation becomes much clearer. As more and more of the education system moved under the control of unelected technocrats and impersonal systems of testing and accountability, the majority became convinced that education was no longer working in their best interests. They rebelled and empowered persuasive populists to return majority control but, instead, populists have worked to break the system entirely as part of a larger project that Edenhofer and Gratton call “democratic backsliding.”

While some governments may only wish to rein in the power of technocrats, others may pursue such reforms to concentrate power in their own hands and, in the process, undermine democratic norms. These concerns have a long lineage in democratic theory: from Polybius to Montesquieu, scholars have emphasized the importance of institutional constraints on the will of the (current) majority as essential for the survival of democracy.

p.17

We have only to look at states like Florida or Oklahoma where the technocrats are not gone but are instead under direct supervision of governors or state school superintendents with expansive power who run the education systems as an extension of their personal ideological agendas.

This brings us back to Martin Gurri’s concept of revolts as ultimately ineffectual or, perhaps more accurately, unable to establish a new order. Because the public is lives in a digital soup of competing ideas and claims about education, they are beginning to exist in a state of perpetual dissatisfaction. No sooner do we get reforms propelling Mississippi’s 4th grade readers to the top of the nation’s NAEP scores than we get the Mississippi legislature passing universal school vouchers to move kids and funding out of public schools. We all listen to Emily Hanford’s podcast about the need for explicit systematic phonics instruction and eventually get enough activism and attention to force states to mandate phonics instruction by law, only for viral articles to public attention to turn toward the lack of reading whole books. At the same time, we’re told that, actually, elementary curriculum should focus on knowledge building and phonics will only take us so far. Hot on the knowledge building heels, here comes the Science of Learning whose advocates want to see states require all instructional training and design to adhere to the ideas of information processing theory.

In some cases these projects are not mutually exclusive. In other cases they are. In all cases what we have is upset with the inability of schools to implement the preferred policies of the advocates, policies they can all bring up studies and articles and testimonials to support. This upset, Gurri tells us, will not go away just because one approach or another takes center stage and implements reforms. People will still be surrounded with digital media explaining shortcomings and drumming up outrage. That insight, the perpetual outrage, is something that adds some needed texture to the technocratic vs majoritarian framework. The majority is always going to be operating in an information environment in which schools are said to be doing something wrong. The public will remain outraged whatever the regime.

In my view, the only way out is for people to have confrontations with reality. Their lived experiences of public schools should be experiences of democratic responsiveness. Parents need to feel like they have a say and that requires attenuating the harshness of technocratic systems set up by the states. We should delegate accountability processes to local districts or, as is the case with Mississippi, build significant flexibility into the accountability system so that these systems target students for interventions rather than justify collective punishment. Advanced courses shouldn’t be subject to strict gatekeeping or locked behind administrative burdens. Parents need to feel like sending their kids to public school gives the kid options and the parents a chance to guide their students through the system, rather than react to its impersonal and unaccountable operations. If we don’t do this, if public schools remain under the purview of technocrats and parents remain on the outside, then we should expect the outrage to continue, the populists to win, and for public schools to continue to wither.